Kenan Camurcu

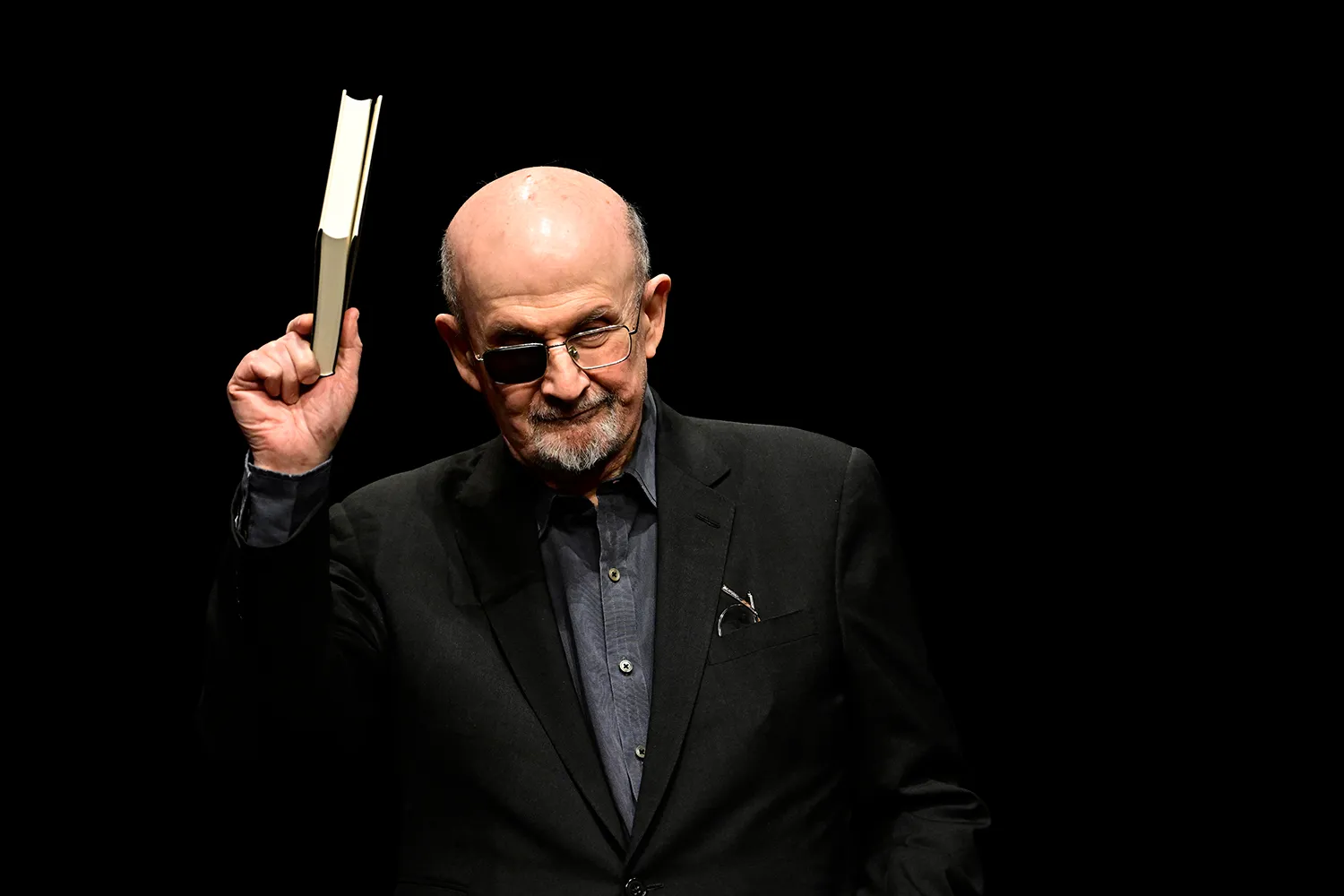

Even without seeing the book The Satanic Verses (1988), Ayatollah Khomeini (1989) issued a fatwa for Salman Rushdie's death in 1989, claiming "insult to Islam" (see The New Yorker article). Rushdie, chosen as a sacrifice by Khomeini to unite the Sunni world against the West and lift Iran out of isolation, was severely injured in August 2022 during a literary event by a knife attack from Hadi Matar, a Lebanese-American Shi'ite and Hezbollah sympathizer. Rushdie lost his right eye.

Rushdie, whom Khomeini issued a death fatwa against and on whose head Tehran placed a bounty, having been employed by Khomeini to religiousize the secular 'Palestinian cause' and serve the purpose of consolidating the 'ummah's unity against the West, was a close friend of Edward Said and a fervent defender of the 'Palestinian cause' long before Khomeini. 1986 interview with Said discussing Palestine, where Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish's poem "The Earth Is Narrow for Us" was also read, went viral in 2022 after the knife attack (see X post).

We cannot assume that Iran's new rulers, due to the limited capabilities of the analog era, failed to sufficiently investigate who Rushdie was. Among the various and probable theo-political justifications for the fatwa, there was certainly the aim to compensate for the internal public disappointment caused by the Iran-Iraq War ending without the promised overthrow of the Saddam regime and without a clear victor (1988), and to prevent this situation from destabilizing the post-revolutionary government. Externally, by issuing a killing fatwa, "new Iran" probably aimed to raise the stakes and lead the Sunni reaction to prevent the deep rift caused by the war between the two Sunni and Shi'ite states from becoming permanent to Iran's disadvantage. Furthermore, by targeting Rushdie, a symbolic figure of the Palestinian issue, "new Iran" might not have wanted to miss the opportunity to get rid of the secular "Palestinian cause." Because with the religious politicization of the Palestinian issue, Tehran became the new center of Amin al-Husayni's antisemitic and fascist struggle legacy.

The Attacker's Presumption of Innocence: "Attack on Islam"

The attacker, Matar, stated in court that Rushdie, who had been involved in the "Palestinian cause" for much longer than Matar's age, attacked Islam, and he declared himself innocent. This implicitly meant that the knife attack should be seen as legitimate and acceptable, much like Hamas's attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, which randomly killed 1200 Israeli civilians, was expected to be justified and widely supported globally. It turns out how many people were ready and eager to repeat the genocide against Jews. Matar's demand for a presumption of innocence from the court was an interesting moment regarding the truth of Islam, which Said's Orientalism theory sought to prove innocent by blaming the Western perception of Muslimness.

There is no doubt that the attack on Rushdie was an act many Muslims from various countries eagerly wished to carry out. Sunnis enthusiastically supported Matar, regardless of his Shi'ite background. Is it not tragic for the sake of Islam that Sunnis and Shi'ites could so easily unite, setting aside their numerous conflicts, over the issue of a deadly attack on a writer in a literary setting? For the sake of Islam, which prides itself on having made brilliant contributions to humanity's scientific progress, thought, philosophy, literature, and architecture. However, it's not entirely accurate to attribute those contributions to Islam itself. The very same Islam that made the world a living hell for the authors of those scientific, philosophical, and artistic endeavors, and even murdered them.

Can a Fatwa to Kill an Apostate Be Respected in the Universe of Law?

Khomeini, in his declaration calling on the Islamic world to "execute" (infaz) Rushdie wherever they found him, cited his apostasy (irtidād) as the justified reason for his killing. In emphasizing this point, he invested in the common ground found in the sources of both Sunni and Twelver Shi'ism that apostates should be killed.

Muslims who react to Westerners with accusations of Islamophobia, disrespect for Islam, hatred of Muslims, etc., expect this oddity to be accepted in the West. They accuse those who advocate for values such as law, human rights, freedom of belief/thought, and expression, stating that such things are unacceptable, of producing Islamophobia. Islam is a religious universe that claims all people of other religions, beliefs, and thoughts are deviant, and only Islam is true and valid, expecting this certainty to be confirmed by everyone. Are those who find this a psychiatric case wrong?

Muslimness with an Execution Tariff for Every Criticism of Religion

Rushdie is actually an ordinary example, as there are others who have been targets of the same hatred and anger. For instance, in 1947, in Iran, the Fadāʾiyān-e Islam organization, led by the famous cleric Navvab Safavi, murdered the philosopher Ahmed Kasravi in the courtroom where he was being tried for insulting sacred figures due to his critical articles on Shi'ite Islam. In 1985, the Sudanese thinker Mahmoud Muhammad Taha was executed on charges of apostasy. In 1992, Farag Fouda in Egypt was assassinated after being accused of apostasy by a court.

In 1993, Nasr Hamid Abū Zayd, an Egyptian, was accused of apostasy by a court. He was forced to emigrate to the Netherlands due to death threats. It was good that he left, because his compatriot Sheikh Shahḥātah, who had converted from Sunnism to Shi'ism, was lynched to death in 2013 by an attack of 3,000 people, which the police merely observed. In 2011, Rafiq Tağıyev in Azerbaijan died after a knife attack following a death fatwa by Iranian Ayatollah Lenkerani for his criticisms of Islam. The championship goes to Bangladesh: between 2013-2015, five writers were murdered in the streets. The list goes on, and none of these are isolated incidents.

Demonstrations to Turn Europe into Afghanistan

When Said published Orientalism (1978), the Islamist organizations' surge of violence had not yet begun, allowing him to comfortably blame the West. With the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the Muslim world entered a completely different trajectory that would force him into endless explanations and corner him. Al-Qaeda, which emerged in Afghanistan, was a source and training camp for radical Sunnism. Foreign fighters returning to their countries from there radicalized Islam in those places. Soon after, bombs began to explode in Western capitals.

Perhaps Said regretted comprehensively blaming the West and completely exonerating Muslimness when he witnessed the accelerating events. Given his strong objections to all examples of violence, an unacknowledged regret is at play.

Nowadays, in European capitals, Muslims are holding Sharia demonstrations aiming to destroy the hard-won democracies, freedoms, high quality of life, and human and animal rights standards, reducing those countries to the level of Afghanistan, Iran, or Turkey. They continuously produce videos convincing themselves that Western countries, where they have lived happily and prosperously for years, enjoying the blessings of law and freedom and earning tons of money, are terrible places, while their own countries are paradise. Yet, they never consider leaving the "hell" they are in and returning to their "paradise" countries.

Muslim Identity: Ethno-Symbolism of Opportunity Seeking in a Conquest-Oriented Climate

Muslims are a community that embraces moralism instead of morality, and Islamism instead of Islam. Their assumed behavior is a constant violation of social protocol. I will repeat tirelessly: In al-Ḥujurāt 14, they are individuals of the lowest level, possessing the characteristics of tribes who were not allowed to call themselves believers because the feeling of certainty in God's existence (īmān) had not yet taken root in their hearts. They could only say they were Muslim, meaning their situation was merely about joining the Arab peace (pax-Arabiana).

The category in al-Ḥujurāt 14 refers to the majority who are neither certain of God nor trusted themselves. Those who, even before the Prophet's funeral was buried, gathered in the consultation council of the Banu Saʿīda's Portico (saqīfah) from the pagan era and hastily elected a caliph. While the state of being a believer defines walking alone towards perfection in spirituality and morality, the dynamic that creates Muslim identity is the state of dissolving into the crowd: the ethno-symbolism of opportunity seeking in a conquering/imperial climate.

Muslimness is the identity of individuals accustomed to collective behavior and educated in uniformity. It is Comtean collectivity. It is imitation (taqlīd). It is a set of religious beliefs and behaviors learned through imitation. This is its difference from belief (īmān), which requires verification (taḥqīq), research, and contemplation. As described by Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq: "Do not be deceived by their prayers and fasting. For they are so engrossed in prayer and fasting that if they abandon them, they would fall into depression from the feeling of emptiness" (Al-Kulaynī, 1988: 2/104, narration 2).

The unique, free, independent solitude of the believing individual hinders discipline. Fiqh, which is the algorithm for dominating life, does not work for them. They must be disciplined with Muslimness so that they can be kept under control, subdued, and made to submit. This way, constant brute force will not be necessary. This is also the reason for Sunni orthodoxy's reaction to libertarian heterodoxy. It is for this reason that their hand is on the trigger, in ambush, to destroy alternative sources of knowledge, belief, and behavior. Because an individual who becomes free through a different interpretation can step outside collective behavior.

For Muslimness, survival is important, not truth. The survival of identity and its political body is much more significant than truth and the search for truth. This explains its high sensitivity to protecting official doctrine. Otherwise, it should not care what different views, interpretations, explanations, etc., anyone might offer.

Becoming Ordinary Within a Collectivity Substituted for Individual Evolution

The Tarāwīḥ prayer is a good example here. The Prophet advised his community to perform voluntary night prayers during Ramadan by themselves, slowly, resting, contemplating, and engaging in remembrance (dhikr). But Caliph Umar transformed Tarāwīḥ into a collective prayer performed in congregation with a specific order and discipline. It was no longer an exercise in perfection for the believing individual but a ritual of ordinary assimilation within the Muslim identity. When faced with the objection that this was an innovation (bidʿah), something newly invented and entirely different, changing what the Prophet did, he said, "Yes, but it is a beautiful innovation" (Al-Bukhārī 2010, Ibn Khuzaymah 1100).

Sunnism, which chose Umar's path, disregarded the Prophet's warning and divided innovations into "beautiful" and "ugly." Ibn Abd al-Barr even ventured to speculate on the Prophet's intention by suggesting that Umar united people behind a single imam instead of division and thus established as sunnah what the Prophet approved (Ibn Abd al-Barr, 2010: 3/515). However, not everyone thought like him. Not even Caliph Umar's son, Abdullah ibn Umar. He considered his father's addition to the morning adhān ("prayer is better than sleep" - al-salātu khayrun min al-nawm; Ibn Abī Shaybah, 2006: 2/326, 2171) an innovation. When he went to the mosque to pray and heard the muʾadhdhin adding to the adhān, he reacted by saying, "Let's leave, because this is an innovation," and left the mosque (Al-Tirmidhī 198, Abū Dāwūd 538).

Umar, who never spoke before gaining political power but began expressing opinions and even making changes regarding religious practices after becoming caliph, means nothing less than examples of political authority's interference in religion. Muslims who saw no harm in his addition of a phrase to the morning adhān are essentially granting the authority the right and power to make changes in religion.

The foundation of the Muslim socio-political identity was laid by the first caliph, ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Quḥāfah (Abu Bakr). It was the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, who transformed it into an ideological and theological identity through imperial advances. The "Muslim" identity was formed by militarization through conquests and financed by spoils of war. The third caliph, Uthmān ibn ʿAffān, reshaped the political heritage he inherited from his predecessors by religiously sanctifying Umayyad clan traditions. Finally, the fifth caliph, Muʿāwiyah, brought the existing political accumulation to its natural conclusions and institutionalized it with a Byzantinist state model. In this historical summary, the five-year rule of Ali ibn Abi Talib (656-661), the only caliph elected by the people after the revolution (June 656) that ended the political regime established by the first three caliphs, was a desperate resistance aimed at preserving and reviving the Prophet's style, which ended in failure and could only be recorded as a small parenthesis in history.

The Riddah Wars: Opening the Chapter of Killing Apostates

The inventor of punishment by killing on charges of apostasy in the history of Muslimness is the first caliph, ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Quḥāfah. His caliphate is full of examples of him executing leading figures who did not pledge allegiance to him and separated from the community he governed. Muslims try to justify Caliph Abu Bakr's attacks on tribes under the heading of "Riddah wars" (wars of apostasy). However, not all of these tribes had apostatized. They were against ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Quḥāfah (Abu Bakr) being hastily made caliph after the Prophet's death, even before his burial, despite ʿAlī having been declared caliph by the Prophet much earlier, and they refused to pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr (Al-Dihāqī, 2001: 34).

Moreover, the apostates did not declare war on Medina; fighting them simply because they abandoned their religion was illegitimate. For example, the Prophet did not declare war on Musaylimah, who gathered thousands of people around him, including those who abandoned Muslimness, despite Musaylimah claiming prophethood.

Musaylimah (Musaylimah ibn Ḥabīb), who declared himself a prophet while the Prophet was alive, claimed in a letter sent to the Prophet that the Qur'an came to Muhammad because the Quraysh were a rebellious people, and he demanded that the Hijaz be divided equally between the two prophets. The Prophet only replied to Musaylimah: "In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. From Muhammad, the Messenger of Allah, to Musaylimah, the liar. Peace be upon those who follow guidance. Indeed, the earth belongs to Allah; He grants it as inheritance to whom He wills of His servants. And the [best] outcome is for the righteous" (Ibn Isḥāq, 2004: 1-6/667).

Three Categories Opposed to the Government of the "New Medina"

Al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897) divided those who did not recognize the government of the "new Medina," which began with Abu Bakr's caliphate, into three groups. One group pursued claims of prophethood. Another group apostatized and crowned themselves (i.e., declared independence). And there were those who did not want to pay zakāt to Abu Bakr (Al-Yaʿqūbī, 1900: 2/128). The commentator of Al-Bukhārī, Al-ʿAynī, claims that this last group performed prayers but denied zakāt, and argues that they were "ahl al-baghy" (rebellious, vandal, aggressor) with whom one should fight (Al-ʿAynī, 2001: 8/352). This is the group about whom Abu Bakr said, "If they withhold from me a rope's length of what the Prophet used to take from them, I will fight them" (Al-Bukhārī 1399).

Al-ʿAynī's interpretation is, of course, a forced one, resorted to in order to baseless justify suppressing political opponents by force. According to Al-Ṭabarī's narration from Abū Mikhnaf (d. 773), not a single one of the tribes who did not pledge allegiance apostatized from Islam (Al-Ṭabarī, 2011: 2/261).

The tribes' justification is narrated as follows: "We will not give zakāt to Abu Bakr. Because Allah said to His Prophet: 'Take from their wealth a charity by which you purify them and cause them to grow, and invoke [Allah's blessings] upon them. Indeed, your invocations are reassurance for them.' [Al-Tawbah 103] We will not give our zakāt to anyone other than the one whose prayer will grant us peace" (Ṭāwūs al-Ḥusaynī, 1979: 436).

The reason for Ashʿath ibn Qays, chief of the Kindah tribe in the Ḥaḍramawt region, rejecting Abu Bakr's call for allegiance through the regional governor and zakāt collector Ziyād ibn Labīd, actually explains the attitude of the opponents: "When all people gather (around him), I will also be but one of them" (Ibn ʿAsākir, 1995: 9/128).

The Asad and Fazārah tribes said, "By Allah, no. We will never pledge allegiance to Abū Faṣīl (Abu Bakr)" (Al-Ṭabarī, 2011: 2/261).

"Abū Faṣīl" was a nickname used to mock and insult Abu Bakr (Haykal, 1942: 116). While "Bakr" means "young camel" (Al-Jawharī, 2009: 107, b-k-r entry), "faṣīl" means "a weaned camel calf that has lost its way" (Al-Jawharī, 2009: 891, f-s-l entry). "Abū Faṣīl" was Abu Bakr's nickname during the pre-Islamic era (Jāhiliyyah). When Abū Sufyān heard the news of the Prophet's death, he asked, "Who will take charge?" When they said "Abu Bakr," he used his pre-Islamic nickname, saying, "Abū Faṣīl? I don't think he will succeed without bloodshed" (Al-Balādhurī, 1959: 1/589).

"Why Did You Exclude the Ahl al-Bayt from This Matter?"

Ḥārith ibn Muʿāwiyah, one of the respected figures of the third generation, after a long discussion with Ziyād regarding allegiance to Abu Bakr, asked the crucial question: "Tell me, why did you exclude his (Ahl al-Bayt) from this matter? Even though they were the most deserving of people?" Ziyād's answer was a picture of helplessness: "The Muhājirūn and Anṣār are in a better position to appreciate this than you." Ḥārith's objection to this answer could be the theme around which all events would revolve if a historical film were to be made: "By Allah, no. The reason you excluded his Ahl al-Bayt from this matter is nothing but your envy. My heart is not convinced that the Messenger of Allah departed this world without appointing someone knowledgeable to be followed. Get out of our sight, man, for you are calling to something unacceptable."

He then recited a poem. The striking line in the poem is: "If the son of Abū Quḥāfah (Abu Bakr) becomes the leader / Then tyranny has come with his leadership." Upon this, ʿArfajah ibn ʿAbd Allāh said: "By Allah, Ḥārith speaks the truth. Your friend is not worthy of the caliphate and does not deserve it for many reasons. Neither the Muhājirūn nor the Anṣār can appoint anyone better for this ummah than the Messenger of Allah" (Al-Wāqidī, 1990: 176-177).

The tribes who came to Medina performed prayers, accepted zakāt, but did not want to give zakāt to Abu Bakr. They cried out: "We obeyed the Prophet when he was among us. How astonishing, who is this king Abu Bakr?" (Ibn Kathīr, 1978: 6/311).

Let's leave the pressures and political assassinations targeting opponents during the caliphates of Abu Bakr and Umar for another article.

Twelver Shi'ism's Efforts to Resemble Sunnism

Twelver Shi'ism's rate of affirming dogmas in an attempt to be accepted by the Sunni majority brings it quite close to Sunnism. For instance, despite believing that the first caliph, ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Quḥāfah, usurped ʿAlī's right to the caliphate, they refer to his wars against political opponents as "Riddah wars," just like the Sunnis. That is, wars against apostates. Khomeini and his successors declared it forbidden to touch the sacred figures of "our Sunni brothers" on the grounds that it would disrupt Muslim unity. The Iraqi Ayatollah al-Sistani, who opposes the Wilāyat al-Faqīh theory, also holds this view. These statements undoubtedly stem from an understanding of getting along well with the Sunni population in their own countries. However, when what Sunnis or Shi'ites consider sacred is assumed to be untouchable and critical thinking is forbidden, the effort to find truth becomes devalued. Scholarly research turns into criminal activity. Art, literature, and philosophy become impossible.

Despite The Lady of Heaven, a film narrating the life of Lady Fatima, having thematic consistency with sources respected by Sunnis in most historical events, excluding its cinematic shortcomings and flaws in presenting supernatural myths as reality, it was protested with the accusation of "insulting Islam's sacred figures" (sacred figures?). The cinema chain Cineworld succumbed to the pressure and removed the film from screening. England also wants no unrest within its borders. In moments of tension, the positivist idea of order immediately bursts forth and can dismantle the liberal, democratic, and libertarian environment with all its tyranny.

The shrewdness in protesting the film, which reflects Fatima's reaction to the first caliph, Umar's leadership of forty men raiding Fatima's house, and other events as described in the sources, with the accusation of "insulting Fatima" (Milat Gazetesi article), should not be overlooked either.

The Pretext for Censorship in the West: "Muslim Sensitivities"

The Western world normalizes censorship and prohibition by citing "Muslim sensitivities," supports opposition to freedom of expression, and can suspend the most fundamental values of Western civilization. For example, it rejects drawing or portraying the Prophet in films based on detailed descriptions in sīrahs, histories, ḥadīths, and special books called shamāʾil-i sharīf, on the grounds that Muslims do not condone it. You cannot even get artificial intelligence to create a portrait of the Prophet with the available information, citing "Muslim sensitivities on this matter."

If someone were to say that Westerners act this way not out of respect but because they want the Muslim universe to remain closed within itself, it would not seem like a conspiracy theory to me at all. What is called "Muslim sensitivity" regarding depictions has no basis in religious sources. It's an unfounded claim. If it was not an issue and was not forbidden during the Prophet's lifetime, who has the authority and power to forbid his portrait from being drawn after his death? On the contrary, it seems more like a planned operation by those trying to make the Prophet forgotten.

A Religion That Kills Apostates Is Insecure

A religion that kills those who cease to believe is insecure. It tries to maintain its existence and unity through deterrence and intimidation. This is a method of maintaining order and preserving survival, as seen in Rome, the Ottoman Empire, and the West during the two World Wars, by executing those who deserted from the army or evaded war.

For a long time, Muslimness has been attempting to silence critics, intimidate and suppress opponents, and weary societies through political assassinations. The absolute Wilāyat al-Faqīh regime in Iran, despite claiming Shi'ism and opposing Abu Bakr's caliphate, demonstrates its full adoption of his practices, and even those of Muʿāwiyah (whom they curse), by filling prisons with political opponents. It is a regime where those who call for Khamenei's resignation are arrested in dawn raids and tried with decades of imprisonment. Even the slightest criticism, protest, or objection can be punished with execution on charges of "spreading corruption on earth." If we were to list examples, pages would not suffice. The situation in Turkey is a perfect symmetry of this.

Sunni or Twelver Shi'ite Muslimness is now antimatter in the current world. An anti-hero. In the Ramy series, written and starred in by Ramy Youssef, when a girl from the friend group was dying from an overdose in her room, Ramy breaking down the locked door with a cry of "Allahu Akbar" to save her was, of course, interesting and impressive against the backdrop of horrific examples where the takbīr is used. However, there is no real-life example or counterpart where the takbīr works for the benefit of humanity. Not even a Muslim who was enthralled by the romance of the fiction in the series emerged. Because takbīr is the password for collectively slaughtering innocent men, women, and children.

Under these conditions, Said's Orientalism is the propaganda currently being spread under the name of Islamophobia, filtered through the sieve of social sciences. Can Hamas's and similar organizations' rejection of terrorist activities be considered a mitigating factor in order to exonerate the theory of Orientalism?

Translated by Gemini

References

- Akbaş, Beyaz Arif. (2014). Postkolonyalizm Denemeleri, YGY (Quoting from R. Radhakrishnan’s “A Said Dictionary”)

- Akınhay, Osman. (2007/2). Mesele Kitap Dergisi. Issue: 9, September, pp: 47-50.

- Arlı, Alim. (2003). “Dünyalar arasında: Edward W. Said’in mirası,” Divan İlmî Araştırmalar, no. 15, pp. 169-189.

- Al-ʿAynī, Abū Muḥammad Badr al-Dīn. (d. 1451). (2001). ʿUmdat al-Qārī Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah.

- Al-Balādhurī, Aḥmad Yaḥyā. (d. 892). (1959). Ansāb al-Ashrāf. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif.

- Al-Bukhārī, Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl. (d. 870). (2002). Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Dār Ibn Kathīr, Beirut.

- Bulut, Yücel. “Edward W. Said'e ve Oryantalizm'e dair.”

- Al-Jawharī, Abū Naṣr Ismāʿīl ibn Ḥammād. (d. 1007). (2009). Ṣiḥāḥ, Tāj al-Lughah wa Ṣiḥāḥ al-ʿArabiyyah. Cairo: Dār al-Ḥadīth.

- Al-Dihāqī, ʿAlī Ghulāmī. (2001). “Janghā-yi Irtidād wa Buḥrān-i Jāneshīnī pas az Payambar,” Maʿrifat, Issue 40, Tehran Shamsi, pp. 34-42.

- Abū Dāwūd, Sulaymān ibn al-Ashʿath. (d. 889). (1997). Sunan Abī Dāwūd. Dār Ibn Ḥazm, Beirut.

- Haykal, Muḥammad Ḥusayn. (d. 1956) (1942). Al-Ṣiddīq Abū Bakr. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif.

- Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr. (d. 1071). (2010) Al-Tamhīd li-mā fī al-Muwaṭṭaʾ min al-Maʿānī wa al-Asānīd. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah.

- Ibn ʿAsākir. (d. 1176). (1995). Tārīkh Madīnat Dimashq. Beirut: Dār al-Fikr.

- Ibn Abī Shaybah. (d. 849). (2006). Muṣannaf. Jeddah: Dār al-Qiblah li-s-Saqāfah al-Islāmiyyah.

- Ibn al-Athīr. (d. 1233). (1966). Al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir.

- Ibn Khuzaymah, Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq. (d. 923). (1992). Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Khuzaymah. Riyadh: Al-Maktabah al-Islāmī.

- Ibn Khuzaymah. (d. 924). (1980). Beirut: Kutub al-Islāmī.

- Ibn Isḥāq. (d. 768). (2004). Al-Sīrah al-Nabawiyyah. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah.

- Ibn Kathīr, Ismāʿīl ibn ʿUmar. (d. 1373). (1978). Al-Bidāyah wa al-Nihāyah. Beirut: Dār al-Fikr.

- Jhally, Sut. (2016). “Edward Said ile Oryantalizm'e Dair,” Trans. Adem Köroğlu, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 41, pp. 167-178.

- Keyes, Ralph. (2021). Hakikat Sonrası Çağ (The Post-Truth Era). Tudem.

- Al-Kulaynī, Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb. (d. 941). (1988). Al-Kāfī. Tehran: Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyyah.

- Parla, Jale. (1985). Efendilik, Şarkiyatçılık ve Kölelik (Mastery, Orientalism and Slavery). İletişim Yayınları.

- Said, Edward W. (1998). Oryantalizm (Doğu Bilim) - Sömürgeciliğin Keşif Kolu (Orientalism - The Reconnaissance of Colonialism). İrfan Yayınevi.

- Al-Ṭabarī, Muḥammad ibn Jarīr. (d. 923). (2011). Tārīkh al-Umam wa al-Mulūk. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah.

- Ṭāwūs al-Ḥusaynī, ʿAlī ibn Mūsā. (d. 1266). (1979). Al-Ṭarāʾif fī Maʿrifat Madhāhib al-Ṭawāʾif. Qom: Maṭbaʿat al-Khayyām.

- Al-Tirmidhī, Abū ʿĪsā Muḥammad. (d. 892). (2000). Ṣaḥīḥ Sunan al-Tirmidhī. Maktabat al-Maʿārif, Riyadh.

- Turanlı, Gül. (2017-1). “Edward Said'in Oryantalist Söylem Analizi,” Şarkiyat Mecmuası, Issue 30, pp. 101-119.

- Al-Wāqidī, Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar. (d. 823). (1990). Kitāb al-Riddah, pp. 176-177, Beirut: Dār Gharb al-Islāmī.

- Al-Yaʿqūbī, Ibn Waḍiḥ. (d. 897). (1900). Tārīkh al-Yaʿqūbī, Beirut: Dār Ṣādir.

0 Comments