Kenan Camurcu

In their 1962 work on research methodology, "The Modern Researcher," Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff provide an instructive example concerning analytical historiography. (Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff, The Modern Researcher, p. 89)

In the summer of 1954, Clare Luce, the US Ambassador to Italy, began to complain of anemia and fatigue. However, her complaints and discomfort disappeared when she left the country. The incident was reported in the press as: "Clare Luce's illness is due to arsenic found in her Rome villa." According to the news, tests indicated arsenic poisoning, but there was no perpetrator of this attempt. This was because, presumably, the poisoning originated from the paint on the ceiling. Due to a laundry operating on the floor above the Ambassador's residence, particles of paint were falling from the ceiling, and the Ambassador was being poisoned by inhaling them.

According to Barzun and Graff, given the manner in which the event was reported and the reliability of the reporters, there seemed to be no reason to doubt this information. However, they draw attention to a neglected detail in the incident: The State Department, the Central Intelligence Agency, and any Italian source had not confirmed this news. Furthermore, it is difficult to believe that the US Ambassador lived in a house so old that paint was falling from the ceiling and had a laundry operating on the floor above. With a little medical knowledge, it could also be determined that the poisoning was not from arsenic, but from lead arsenate, which was used in paints at the time, and that this substance would manifest with different symptoms.

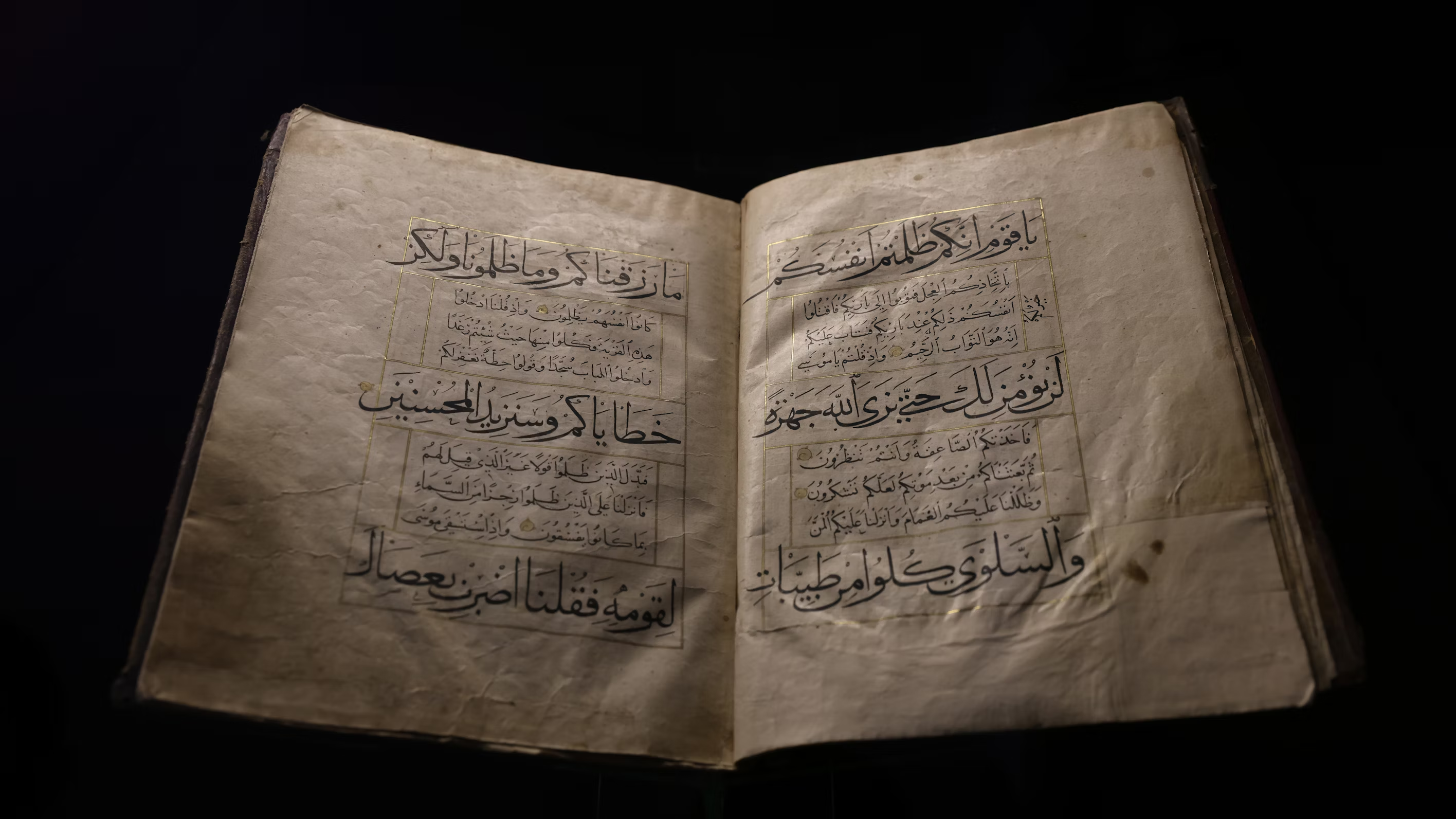

The importance of scrutinizing incoming information against criteria such as logic, consistency, and conformity with the flow of life is clearly demonstrated in this example. Relying solely on techniques that measure the reliability of the transmission path of information, without a critical method, will perpetuate erroneous conclusions. This judgment also applies to the historiography of the early period of Islamic history. The writing of sīra in the Islamic tradition is no different from the theocratic and mythos-centric historiography of ancient Greece (R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History, p. 46).

The problem with sīra writing concerning the early period of Islam is that it is not analytical and possesses romantic characteristics. Therefore, the scientific method advice of the authors of The Modern Researcher to Western historiography—"Historiography must now cease to be moral and political and become scientific. Knowledge and evidence must take precedence over literary ability"—is also applicable to sīra writing.

Traditional historiography consists of the mere transmission of past events. It is subjective and provides raw material for the science of history. Scientific history, on the other hand, is the history of past events that has been verified and proven (Abdullah Laroui, Historicism and Tradition, p. 7).

Scientific history conducts an objective analysis of historical material within cause-and-effect relationships. For minds possessing powers of reasoning and analysis, there is a rich archive of information available. What is important is to have the curiosity, desire, and passion to journey into these archives of time. As Ursula K. Le Guin put it, "The true journey is a return. You may know a little more when you get back there than you did when you started." (David Streitfeld, Ursula K. Le Guin, The Last Interview and Other Conversations, p. 164)

Historical knowledge is the knowledge of what the mind has done in the past, and it is also the re-enactment of this, the continuation of past activities in the present (R. G. Collingwood, p. 261).

Historiography is not a hobby. In the Western intellectual tradition, where it is believed that each generation must rewrite history in its own style, the British philosopher R. G. Collingwood (1889-1943) regarded this not as a simple fact of life, but as an obligation (Dennis W. Harding, Rewriting History: Changing Perceptions of the Past, p. 263). This obligation is also an indispensable duty for the rectification and purification of history that has been speculated upon and has led to social polarization.

The fundamental problem of historiography is the impartiality of the witnesses from whom information is transmitted, or their inability to be abstracted from their own circumstances (Carr Hallet Edward, What Is History?, p. 92). Even the historian himself may not be able to act impartially. However, this problem is not insurmountable. Questioning the accounts of historical witnesses with other testimonies and asking the right questions about the transmitted information will lead the historian to reliable conclusions. The historian's subjectivity, if the researcher's honesty is trusted, does not necessitate a level of skepticism that would overshadow the research. The Italian historian and socialist politician Gaetano Salvemini (1873-1957) used to advise his students: "Impartiality is a dream, honesty is a duty." (Stanislao G. Pugliese, Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile, p. xvii).

In the existing historiography of the early period of Islam, which is based on narratives (sīra), neither the principle of impartiality was observed nor were scientific methods and questioning techniques employed. The only difference between the historical/sīra sources written starting from Ibn Ishaq (d. 151/761) and hadith narration is that the reports are combined in a historically appropriate flow. In this mode of narration, instead of focusing on events and material causes and the relationships between them, the focus was on individuals in accordance with political preference. Classical and modern Islamic histories are advanced examples of romantic historicism.

M. Fuad Köprülü (1890-1966) complained about the fact that narratives of rulers and viziers, wars and victories, rebellions and revolutions, which should have been considered exceptions from a historical perspective, were being treated as history itself, and he encouraged the writing of social history in accordance with rational working methods. Only by doing so could the era of romantic history be brought to a close (Mustafa Oral, Meşrutiyetten Cumhuriyete İktidar Odaklı Aydınlar, p. 37).

In the age of nationalisms, romanticism in the West emerged as historiography aimed at glorifying one's own nation. Germans focused on language and culture, while the French emphasized political victories. This resulted in the nation effectively being elevated to a secular religion (Büşra Ersanlı Behar, İktidar ve Tarih, Türkiye'de “Resmî Tarih” Tezinin Oluşumu 1929-1937, p. 28). The romanticism in sīra writing, in turn, gave rise to sacred history based on the stories of sacralized individuals. It can be argued that Islamic historical studies confined to the realm of theology have not been able to overcome this obstacle of sacredness.

There is a considerable amount of scattered information available regarding the early history of Islam, and its evaluation through the lens of political science (or social sciences in general) will lead to revolutionary renewal in the field of sīra writing.

Official Reaction to the Recording of History

The primary reason for the early history of Islam entering a major tunnel of uncertainty is the destruction of records related to the Prophet's narrations, based on the questionable warning attributed to the Prophet prohibiting the writing of hadith. According to a narration attributed to Abu Sa'id al-Khudri, the Prophet said: "Do not write anything from me except the Qur'an. If anyone has written anything other than the Qur'an, let him destroy it." (Ibn Kathir, Jami' al-Masanid wa's-Sunan, 33/272, Hadith 5805). To this must be added the destruction of the Qur'an text's recorded documents (mushafs) by various methods during the time of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan (d. 656) (Ibn Asakir, Tarikh Madinat Dimashq, 39/245). With the elimination of all these records, which would have been excellent sources for historiography, only historical-oral information, culture, and material remained, to be written down two centuries later.

Despite the Arabic tradition that oral history is as strong and reliable as written history, it is a fact that narrations in chains of transmission suffered linguistic and semantic losses. When we add to this the activity of fabricating narrations (hadith) due to various motives such as ethnic fanaticism, political polarization, and material gain—even though the sciences of hadith and rijal have proven methodological strength in narration analysis—it becomes clear that research is conducted in a difficult and arduous field. Therefore, sometimes when the classical methods and principles of hadith methodology were found to be ineffective, new tools were resorted to. For example, Muhammad Hamidullah (1908-2002), while examining the narrations about the Battle of Uhud, concluded through measurements he made on the battlefield that some narrations could not be authentic (Fatih Erkoçoğlu, "Tarih-Mekân İlişkisi: Uhud Savaşının Mekânı Üzerine Bazı Mülahazalar", C.Ü. İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, June 2011, pp. 319-350).

Just like narrations that clearly contradict Qur'anic verses, those with content that is contrary to the natural flow of life, inconsistent, and illogical should not be considered correct and valid, even if their chain of narration (isnād) appears authentic. This is because, as Allameh Askari (1914-2007) proved, apart from fabricated narrations, there are even fabricated Companions who entered the isnād system. Askari identified one hundred and fifty imaginary Companions whose names appear as narrators in the isnād system, including those claimed to be the Prophet's stepson or Ali's followers (Sayyid Murtada Askari, Khamsun wa Mi'ah Sahabi Mukhtalak, 1969).

It is certain that this confusion was caused by the official reaction to record-keeping shown by the power that emerged in the "new Medina" after the Prophet's death. It is alleged that the Prophet himself forbade the notation of historical events and his own words. However, the fundamental contradiction here is the claim that the Prophet did not forbid the oral transmission of his words but only forbade their writing. The logical flaw in prohibiting writing but not speech seems to have been overlooked. Furthermore, the weak justification that the Prophet forbade the writing of hadith due to the "possibility of mixing with Qur'anic verses" (Ahmet Yücel, "Kitabet", DİA, 26/81) is also contradictory. Were the Companions, who were considered so superior and untouchable that critical historical studies were deemed disrespectful, so unfamiliar with the subject that they could not distinguish between a Qur'anic verse and the Prophet's words? Moreover, the hadith claiming that the Prophet forbade anything other than the Qur'an from being written reached us in written form. Did those who transmitted this warning write it down and convey it to subsequent generations along with the Qur'an, despite the explicit prohibition?

Another motivation for the reaction to recording events during the Prophet's time is proven by the fact that despite the great support given to the writing of Islamic history based on the narrations of Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri (d. 742), who was the main source of Sunni views and pro-Umayyad, the accounts of, for example, Sulaym ibn Qays (d. 76/695), who was pro-Ali ibn Abi Talib (d. 661), were seen as marginal and illegitimate (For the discussion on Sulaym ibn Qays, see: Mehmet Nur Akdoğan, "Kitâbu Süleym b. Kays ve Kaynaklık Değeri", Bitlis Eren Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, December 2014, pp. 1-22).

The Popular Narrative of Early Islamic History

The popular writing of the early period of Islamic history, known as "Asr-ı Saadet" (The Age of Bliss), is a highly refined and sifted mass of information. When the filtered parts are included in history, a picture that would create deep disappointment in minds that have turned official history into a belief might emerge. Therefore, the reason for not touching the past is probably an ideological sensitivity regarding the inability to predict what would emerge from critical examination, and that the truth can only stand by being covered up.

The popular narrative of Islamic history is like a school of absolute conviction and blind loyalty. In the historian Mas'udi (d. 956), nicknamed "the Herodotus of the Arabs," we find the historical reference through which we can grasp this socio-psychology: "The unquestioning [blind] obedience of Mu'awiya's men had reached such a point that when he led them to the Battle of Siffin (657), he led the Friday prayer on Wednesday [and no one objected]." (Mas'udi, Muruj al-Dhahab, 3/33). This anomaly, which was limited to Damascus at that time, spread throughout the whole of existing Muslimness with the Umayyad rule that began with Mu'awiya b. Abi Sufyan (d. 680) and lasted for ninety years. When people began to pray and leave the mosque to avoid listening to Ali being cursed in the sermon (Ya'qubi, d. 905, Tarikh al-Ya'qubi, Brill 1883, 2/265), Mu'awiya's innovation (Shawkani, d. 1834, Nail al-Awtar, 7/52), which changed the Prophet's practice of first prayer then sermon for Eid prayers, and placed the sermon first, continued for a long time in established religiosity.

The events that erupted surprisingly immediately after the Prophet's death are not sudden social phenomena. A careful critical and analytical study of historical material will reveal that these incidents had been brewing while the Prophet was still alive and manifested audaciously in the power vacuum that emerged after his death.

Mu'awiya's Byzantinist-metaphysical political regime, established in 661, was a natural consequence of the upheaval in the early period. As long as the truth that swords were drawn immediately after the Prophet's death, that polarization among the Companions escalated into conflict with the participation of new Muslims who had not even had the opportunity to learn Islam, that there were lynching attempts against prominent figures of Islam, and that political opponents were massacred, is swept under the rug, a new and proper beginning will not be possible.

Reconstructive Sīra Writing

Sīra is essentially the reconstructive writing of early Islamic history. Through this method, the events of objective history were rewritten backwards to legitimize political positions. There are many examples that can be given for the ethnic, political, and ideological scheme of this rewriting. In this analysis, we will limit ourselves to three examples.

1) The Use of the Claim of Umar's Marriage to Ali's Daughter for Political Legitimation

In sīra, where imaginary reality forms the backbone, one of the significant indicators of how well the Companions got along is the reports claiming a familial relationship through marriage between Umar ibn al-Khattab and Ali ibn Abi Talib, despite deep disagreements between them. According to these narrations, Umar married Umm Kulthum, Ali's daughter. This marriage is used as proof that Ali and his companions did not oppose the hastily conducted election of the caliph after the Prophet's death.

According to Sunni view, it is certain that Umar ibn al-Khattab married Umm Kulthum, the daughter of Ali ibn Abi Talib, during his caliphate (Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, al-Isabah, Article 1473, 8/275). According to the narration, Umar asked Uthman, Zubayr, Talhah, and Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf to help him marry Ali ibn Abi Talib's daughter. The reason was the Prophet's saying: "On the Day of Judgment, all lineages will be cut off except my lineage." Umar wanted to be of his lineage in addition to being his companion (Ibn Sa'd, Tabaqat, 10/430).

Shi'i scholars, however, have four views:

Umar married Umm Kulthum, Ali's daughter (Muhammad Taqi al-Tustari, Qamus al-Rijal, 12/216). One of the proofs cited for the marriage is that Ali ibn Abi Talib took his daughter Umm Kulthum back into his house after Umar's assassination (Kulayni, al-Kafi, 6/116).

Ali was forced to marry his daughter Umm Kulthum to Umar due to the coercion he faced and at the urging of his uncle Abbas (Sharif al-Murtada, Rasa'il, 3/14). According to a narration, when Imam Sadiq was asked about Umm Kulthum's marriage to Umar, he replied: "She is a girl who was taken from us by force" (Kulayni, al-Kafi, 5/346).

No such marriage occurred. Shaykh Mufid states that the narration regarding Umm Kulthum's marriage to Umar is not established and that Zubayr ibn Bakkar, who transmitted it, was known for his enmity towards Ali ibn Abi Talib (Shaykh Mufid, al-Masa'il al-Sarawiyyah, 86-87). Ibn Shahrashub also quotes Abu Muhammad Nawbakhti: "A marriage contract was made between Umm Kulthum and Umar, but Umm Kulthum was young, so they waited for her to grow up. Umar died before the consummation of the marriage" (Ibn Shahrashub, Manaqib Al Abi Talib, 3/89).

The Umm Kulthum whom Umar married was Umm Kulthum, the daughter of Abu Bakr, not Ali. When Abu Bakr died, his wife Asma married Ali ibn Abi Talib, and her daughter Umm Kulthum moved into Ali's house with her. The Umm Kulthum whom Umar sought from Ali was the daughter of Abu Bakr and Asma. Ali's stepdaughter Umm Kulthum was confused with his own daughter Umm Kulthum. Nawawi, the commentator of Sahih Muslim, when discussing Umm Kulthum, the daughter of Ali ibn Abi Talib, states that Umar ibn al-Khattab married this Umm Kulthum (Nawawi, Tahdhib al-Asma, 2/365, Article 777), but in the section "Aisha's sister," he states that Umm Kulthum, Abu Bakr's daughter, married Umar. Ayatollah Sayyid Mara'shi Najafi also argues that the Umm Kulthum who married Umar ibn al-Khattab was Umm Kulthum, the sister of Muhammad, Abu Bakr's full brother (Sayyid al-Mara'shi, Sharh Ihqaq al-Haqq, 2/490).

2) Politically Motivated Reconstruction of "The Prophet's Daughters"

In the historical reconstruction undertaken to legitimize Uthman's caliphate, two daughters were first fabricated for the Prophet, and then these daughters were successively married to Uthman, thus earning him the title of "the Prophet's son-in-law." However, since Ali ibn Abi Talib was also a son-in-law, it was claimed that Uthman married one of the Prophet's daughters, and after her death, the second daughter, thus making him more virtuous than Ali and acquiring the title of "possessor of two lights" (Dhu al-Nurayn). Yet, in early sources, the epithet "Dhu al-Nurayn" for Uthman is not found at any point in his life, during his selection as caliph, or at his death.

Sunni sīra writers did not ask questions that would allow for the detection of historical falsehoods in a few steps. Instead, the scenario of reconstructive writing was popularized. However, it is striking that after the rebellion that led to the assassination of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan, when the caliph's body was prevented from being buried in the Muslim cemetery (Tabarani, al-Mu'jam al-Kabir, 1/78-79, hadith 109), there was no warning that Uthman ibn Affan, as the Prophet's son-in-law, should have received the necessary respect. If Uthman was the Prophet's son-in-law, the question of why only Hasan and Husayn are known as grandchildren and why Uthman's children are not recognized as "grandchildren" also remains unanswered.

According to the contradictory narrative of political sīra writing, Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum, who were born after the beginning of prophethood, were married to two sons of Abu Lahab. After they divorced them following the degradation of Abu Lahab in Surah al-Masad (al-Bayhaqi, Dala'il al-Nubuwwah, 2/339), Uthman married Ruqayyah and migrated with her to Abyssinia (Ibn Asakir, Tarikh Madinat Dimashq, 39/8). Although the story of migration to Abyssinia is also doubtful, according to the available information, there were two migrations to Abyssinia. The first took place in the month of Ramadan, in the fifth year of the beginning of revelation, by chartering a boat. Uthman and his wife Ruqayyah were also present in this migration (al-Ayni, Umdat al-Qari, 17/16). In this case, how could Ruqayyah, born after the beginning of revelation, be married to Uthman at the age of 5 or younger in the fifth year of revelation? And what about the claim that she was previously married to Abu Lahab's son?

Among the evaluations on the subject, the most striking hypothesis is that Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum are not two separate individuals. Just as Abu Lahab's two sons, Utbah and Utaybah, who are assumed to have married them before Uthman, are not two separate individuals. This confusion is reflected in the sources. While Ibn Sa'd writes that Ruqayyah was married to Utbah (Tabaqat, 10/36, article 4929), Ibn Abd al-Barr records that Umm Kulthum was married to Utbah (al-Safadi, d. 1363, al-Wafi bi'l-Wafayat, 24/271).

There is a suspicious oddity in Ibn Sa'd's mentioning Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum using the same sentences, even down to the phrase "He was not with her (Utbah/Utaybah)." The two biographies are almost repetitions of each other. While it is clear that Abu Lahab's statement "You are forbidden to us" was addressed to one person, this sentence is repeated in the biographies of both daughters. Moreover, the name of the girl referred to as "Umm Kulthum" is not even known. The fact that Utbah and Utaybah, who are claimed to be Abu Lahab's sons, are only introduced in sīra as the first husbands of Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum supports the hypothesis of a history written backward later on.

It is stated that Umm Kulthum migrated to Medina with the Prophet's daughter Fatimah: "Ibn Sa'd says that Umm Kulthum migrated to Medina with Fatimah and other members of the Prophet's family when the Prophet migrated." (Ibn Hajar, al-Isabah, 8/273, article 1462). However, Umm Kulthum's name is not mentioned among those in Ali ibn Abi Talib's caravan: "(When Ali migrated to Medina) he was accompanied by the Fatimas, Umm Ayman and Ayman's children, and a group of the weak among the believers." (Abu'l-Faraj al-Halabi, al-Sirah al-Halabiyyah, 2/72). The "Fatimas" referred to are Fatimah, the Prophet's daughter; Fatimah bint Asad; Fatimah bint Hamza; Fatimah bint al-Zubayr; and Fatimah bint al-Harith (Bakir Emin al-Ward, Ashab al-Hijrah fi'l-Islam, p. 206).

It should be noted that when Fatimah, in her famous Fadak speech in opposition to the caliphate of Abdullah ibn Abi Quhafah (Abu Bakr), spoke of Ali as the Prophet's son-in-law, Uthman was also among those listening to the sermon, but he did not raise the objection that he was also a son-in-law. Fatimah said: "O people, I am Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad (...) He is my father, not your women's. My cousin is not your husband either." (Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Abd al-Aziz al-Jawhari, al-Saqifah wa Fadak, p. 142; Ahmad b. Musa Ibn Marduyah al-Isfahani, Manaqib Ali b. Abi Talib, p. 202).

There is another important detail: Abdullah, Umar's son, when asked to compare Uthman and Ali, mentions only Ali as the Prophet's son-in-law and refers to the public opinion regarding Uthman, stemming from his flight during the Battle of Uhud: "As for Uthman, Allah forgave his sin [referring to his flight from the Battle of Uhud]. But you hated to forgive him. Ali is the cousin and son-in-law of the Messenger of Allah." (Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, hadith 4515, Kitab al-Tafsir).

In Sunni sīra books, apart from Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum (Zaynab) being listed as the Prophet's daughters, there is not a single incident related to these daughters in the Prophet's personal life. None of them, except Fatimah, appear in the Prophet's family life. While Fatimah's name, kunya (teknonym), epithets, and life are narrated in all details, almost nothing is known about the others claimed to be the Prophet's daughters. Sīra writers who dedicate special sections to "The Prophet's Daughters" (Banat Rasulillah) cannot even provide the name of the daughter referred to as Umm Kulthum.

In this case, the question to be asked is: If Umm Kulthum and Ruqayyah were not the Prophet's daughters, who were they?

In response to this question, there is a Shi'a claim. According to the claim of Abu'l-Qasim Kufi, a faqih and theologian of the Imami Shi'a, Umm Kulthum (Zaynab) and Ruqayyah were not the Prophet's daughters from Khadijah but his adopted daughters (Ali b. Ahmad al-Kufi, d. 963, al-Istighathah fi Bid' al-Thalathah, p. 108; Sayyid Ja'far Murtada Amili, al-Sahih min Sirat al-Nabi, 2/218).

According to Kufi's account, the Prophet's wife Khadijah had a sister named Hala, who was married to a man from the Banu Makhzum. When her husband died, she married a man from the Banu Tamim and had a son named Hind from him. This man from Banu Tamim had two daughters named Zaynab and Ruqayyah from his previous wife before Hala. When the man died, his son Hind went to his father's tribe, while the girls remained with Hala. Hala passed away shortly after her sister Khadijah married the Prophet. Ruqayyah and Zaynab grew up in the house of Khadijah and the Prophet. This was because, according to the Arab custom of the time, an orphan was considered to belong to the one who raised him, and a person could not marry them.

3) Seeking Support from the "Slander Against Aisha" Story in Political Polarization

According to the famous narrative, the slander of adultery against the Prophet's wife Aisha (d. 678) in the fifth year of the Hijra (627) was rejected and the truth revealed by verses 11-20 of Surah An-Nur in the Qur'an. All Sunni scholars and some Shi'i scholars argue that Aisha was cleared by these verses. Sunnis do not limit themselves to stating that Aisha was cleared by the verses but also consider this acquittal a great virtue for Aisha. However, surprisingly, there is no narrator of the "slander of adultery" (ifk) incident other than Aisha. It is clearly contrary to the natural flow of life that such an important event, which allegedly shook Medina for a month and involved many other interconnected developments, is narrated by only one narrator.

The narration of Aisha's "slander of adultery (ifk)," which is not found in the early hadith source Muwatta' of Imam Malik (d. 795), became famous because it was repeatedly transmitted and reiterated by others, even though Aisha was the sole source. The naming of the narration as "ifk" appears to aim at asserting that this report was the cause of the slander (ifk) incident described in Surah An-Nur.

Aisha, the sole source, narrated the incident approximately 30 years after the Prophet's death, at a time when anti-Ali propaganda in Syria, propagated by Mu'awiya, was at its peak. It is important to recall that a special section is dedicated to Ali in the slander narration. According to Aisha's claim, Ali was among the group who believed the slander, like the Prophet, and he had urged the Prophet to divorce her immediately.

According to Aisha's account, on the return from the campaign of al-Muraysi' (Banu Mustaliq) in the fifth (or sixth, 627) year of the Hijra, Aisha went away from the caravan to relieve herself. When she returned, she realized she had lost her necklace and spent some time searching for it. Meanwhile, the army did not notice her absence and set off towards Medina. When Aisha returned to the camp, she found no one. A man named Safwan ibn Mu'attal, acting as a rearguard, reached the place where the caravan had camped and saw Aisha sitting alone. He put her on his camel and caught up with the army. The two arriving at the camp together caused gossip in Medina. The Prophet became angry with Aisha. Thereupon, the verses in Surah An-Nur were revealed, proving Aisha's innocence.

Bukhari states that he collected several narrations regarding the event described in this narration, and that these narrations confirm and inform each other (Sahih al-Bukhari, p. 1187, hadith: 4750, Kitab al-Tafsir). Therefore, it can be said that the detailed narration transmitted from Aisha is actually a compilation from several narrations, and not all parts of it were transmitted from Aisha (Sayyid Muhammad Riza Husayni, "Naqd wa Barrasi-yi Tatbiqi-yi Sha'n-i Nuzul-i Ayah-i Ifk ba Ruykardi-yi Tarikhi", Pazhuheshha-yi Tafsir-i Tatbiqi, Spring and Summer 2019, pp. 85-109, p. 94).

Aisha's highly detailed narration is full of irreconcilable contradictions. Briefly summarized, according to the claim in Bukhari's narration, the Prophet was both angry with his wife and abandoned her for a month, and also followed the gossiping crowd by saying, "If you are chaste, Allah will acquit you." However, the verse condemns those who participated in the gossip, and in this case, the Prophet would also be counted among the condemned. In their attempt to emphasize Aisha's acquittal by Allah, the historians seem to have overlooked the grave consequences they caused by raising the bar so high. In fact, it is even claimed that Aisha, upon being acquitted of the slander of adultery by the revelation of the verses, said to the Prophet, who recited the verse, "I will not thank you, I will thank Allah" (Jalaluddin al-Suyuti, al-Durr al-Manthur, 11/680).

Furthermore, in Surah An-Nur, verse 11, there is a grammatical rule that makes the claim that the slander produced and spread by an organized group (usbah) was about Aisha difficult. There is no singular feminine pronoun in any of the verses continuing up to Surah An-Nur, verse 20, that can be interpreted as referring to Aisha.

Another oddity is this: The narration, which purports to establish that Aisha could not have committed adultery, makes Aisha say that Safwan ibn Mu'attal, who brought her to the camp on his camel, was impotent, without having considered how Aisha could have been certain of this. Perhaps this story is a direct copy of how the slander of adultery against Mariyah, the mother of the Prophet's son Ibrahim, which claimed that Ibrahim was actually from her servant Jurayh, collapsed when it was revealed that Jurayh had no male organ (al-Qummi, Tafsir al-Qummi, 2/99). On the contrary, Safwan ibn Mu'attal was married and complained to the Prophet (peace be upon him) that he could not be with his wife because of her excessive worship, saying, "I am a young man, I cannot be patient" (Abi Dawud, 2/84, hadith 2459).

Moreover, although those who slandered Aisha are named in the narration, there is no testimony that the punishment prescribed for slander (qadhf) was applied to them.

There is also an inconsistency in Aisha's statement that she presented her servant Barirah as a witness to her innocence. This is because Barirah had not even started living in Aisha's house during the ifk incident, which is claimed to have occurred in the fifth year of the Hijra, let alone being in Medina. She was bought and freed by Aisha in the 9th year of the Hijra, after Mecca was taken from the polytheists.

Sayyid Murtada Askari, while criticizing Tabari's historiographical method, points out that he did not compare historical events with their time. One of the examples he gives here is the assumption that the slave girl Barirah, whose name is mentioned as a witness in the ifk narration, was present in Aisha's house (Sayyid Murtada Askari, "Naqd-i Metod-i Tabari dar Tarikhgari", Kayhan-i Andishe, Issue: 25 (July-August 1990), pp. 32-45, pp. 35-36).

One of the most important moments narrated in the ifk narration is the Prophet ascending the minbar in the mosque and reciting the verses of Surah An-Nur, which are claimed to have been revealed concerning Aisha. It seems that the narrators who depict the event attributed to Aisha were unaware of a critical mistake they made when describing the Prophet ascending the minbar. This is because the minbar in the Prophet's Mosque was built three years after the ifk verses, in the eighth year. Some even say the ninth year (al-Maqrizi, Imta' al-Asma, 10/95). Abu Abdillah Ibn al-Najjar al-Baghdadi narrates from Waqidi that the minbar was built in the seventh year (al-Durrah al-Thaminah fi Akhbar al-Madinah, p. 130).

Aside from the alleged ifk incident experienced by Aisha, the fact that no one else besides herself narrated her participation in the Banu Mustaliq expedition also refutes the reconstructive sīra writing. No one in the army narrated that she was with them during the campaign. There is not a single witness who narrates that she set off from Medina with the Prophet. This information also has only Aisha as its sole source.

There is also a logical fallacy in the claim that neither the Prophet nor anyone else noticed Aisha's absence for the long hours that passed until Safwan and Aisha caught up with the army when they rested at midday on the 300-plus kilometer return journey to Medina. At that time, an average camel (or horse) walk covered approximately 110 km per day (Donald Routledge Hill, "İlk Arap Fetihlerinde Deve ve Atın Rolü", Marife, April 2012, pp. 139-150, p. 142). The claim that Safwan and Aisha caught up with the army during the midday rest of an army that set out before dawn implies that for approximately 6-7 hours (considering that the sun rose around six o'clock in Shaban, which corresponded to winter in the 5th year of the Hijra), no one, including the Prophet, had any contact with Aisha, and her not leaving the hawdaj (litter) for toilet, fresh air, or any other need during this period did not attract anyone's attention.

The most striking example of historiography interfering with the reason for the revelation of Qur'anic verses and causing a change in meaning is the narration of the ifk incident. The pious intelligentsia, who assume that verses 11-20 of Surah An-Nur contain a definite and clear judgment regarding the slander against Aisha, and who never even consider examining whether this is truly the case, perpetuate a major historical misconception. The "ifk story" proves how an imaginary reality can gradually transform into an absolute truth and form a political, social, and cultural origin for a certain ideology.

Looking at the issue from a different angle, Denise Spellberg notes the recording of the verses in Surah An-Nur as slander against Aisha in history as an unexpected success for a woman in Arab tradition (Denise Spellberg, Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past, The Legacy of Aisha bint Abi Bakr, p. 191).

The reconstructive story is so influential that Spellberg refers to Austrian anthropologist Erika Friedl's study on women in the mountain villages of Buyer Ahmad, Iran (Erika Friedl, Women of Deh Koh: Lives in an Iranian Village), and narrates the interpretation given to the ifk verses by an illiterate peasant woman. The peasant woman removes Aisha and Safwan, who saved her, from the ifk narration and replaces them with heroes from her own environment, narrating and interpreting the verses around the power of rumor and divorce causing bad repute (Jane Dammen McAuliffe (ed), "Aisha bint Abi Bakr", The Encyclopedia of Qoran, 1/58).

Sīra is essentially reconstruction applied to objective history. However, it is certain that relating events through the comparative historical method and from the perspective of general history will increase the success and accuracy rate.

Sīra writers of the second century Hijri, who focused on recording oral information and did not engage in analytical history, may be excused for transmitting this information without critical examination. Ultimately, they made their judgments by looking at the chain of narrators and the isnād of the reports, leaving textual criticism to the hadith scholars. Today, we are in a better position to evaluate the available material with the advanced methods and techniques of historical science. Instead of the difficulties authors in the past faced in accessing each other's works, we are now equipped with the unlimited access possibilities of the internet revolution. Correcting misinformation with the results obtained from in-depth investigations should be an urgent task of our time. The fields of science that should play a role in this task are the social sciences, especially political science.

The writing of Islamic history has dozens of problematic topics, and all of them need to be carefully examined to uncover authentic information. But first, a proper sīra method must be developed. The method that glorifies and references individuals based on fabricated or weak narrations, and then evaluates historical events according to these individuals, is the fundamental reason that corrupts proper sīra writing. Interpreting or attempting to rewrite historical events according to individuals who are assumed to be of high virtue based on narrations falls under romantic historiography, not scientific history. The only basis for politicized sīra is such a historical understanding.

Translated by Gemini

REFERENCES

Akdoğan, Mehmet Nur, "Kitâbu Süleym b. Kays ve Kaynaklık Değeri", Bitlis Eren Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, Vol: 3 No: 2 (December 2014).

Amili, Sayyid Ja'far Murtada, al-Sahih min Sirat al-Nabi (s), Qom: Dar al-Hadith, 2005.

Askari, Sayyid Murtada, Khamsun wa Mi'ah Sahabi Mukhtalak, Fourth Edition, Baghdad: Manshurat Kulliyat Usul al-Din, 1969.

Askari, Sayyid Murtada, "Naqd-i Metod-i Tabari dar Tarikhgari", Kayhan-i Andishe, No: 25 (July-August 1990), pp. 32-45.

Ayni, Abu Muhammad Badr al-Din, Umdat al-Qari Sharh Sahih al-Bukhari, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 2001.

Baghdadi, Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Abd al-Aziz, al-Saqifah wa Fadak, Beirut: Sharikat al-Kutubi, 1993.

Baghdadi, Ibn al-Najjar, al-Durrat al-Thaminah fi Akhbar al-Madinah, Medina: Dar al-Madinah al-Munawwarah, 1996.

Barzun, Jacques and Henry F. Graff, The Modern Researcher, Ankara: TUBITAK, 1996.

Behar, Büşra Ersanlı, İktidar ve Tarih, Türkiye'de “Resmî Tarih” Tezinin Oluşumu (1929-1937), Istanbul: Afa Yayınları, 1992.

Bayhaqi, Abu Bakr Ahmad, Dala'il al-Nubuwwah wa Ma'rifat Ahwal Sahibi al-Shari'ah, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 1988.

Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, Beirut: Dar Ibn Kathir, 2002.

Collingwood, R. G., The Idea of History, Second Edition, Ankara: Gündoğan Yayınları, 1996.

Edward, Carr Hallet, What is History?, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2002.

Erkoçoğlu, Fatih, "Tarih-Mekân İlişkisi: Uhud Savaşının Mekânı Üzerine Bazı Mülahazalar", C.Ü. İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, Vol: 15, No: 1 (June 2011).

Friedl, Erika, Women of Deh Koh: Lives in an Iranian Village, London: Penguin Books, 1991. (Turkish translation: İran Köyünde Kadın Olmak, Istanbul: Epsilon Yayınevi, 2003).

Halabi, Abu al-Faraj Ali, al-Sirat al-Halabiyyah, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 2006.

Harding, Dennis W., Rewriting History: Changing Perceptions of the Past, Oxford University Press, 2020.

Hill, Donald Routledge, Trans: Mehmet Nadir Özdemir, "İlk Arap Fetihlerinde Deve ve Atın Rolü", Marife, Vol: 12, No: 1 (April 2012), pp. 139-150.

Husayni, Sayyid Muhammad Riza, "Naqd wa Barrasi-yi Tatbiqi-yi Sha'n-i Nuzul-i Ayah-i Ifk ba Ruykardi-yi Tarikhi", Pazhuheshha-yi Tafsir-i Tatbiqi, Year: 4, No: 9 (Spring and Summer 2019), pp. 85-109.

Ibn Asakir, Tarikh Madinat Dimashq, Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1996.

Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, al-Isabah fi Tamyiz al-Sahabah, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 1995.

Ibn Kathir, Jami' al-Masanid wa al-Sunan, Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1994.

Ibn Sa'd, Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Cairo: Maktabat al-Khanji, 2001.

Ibn Shahrashub, Manaqib Al Abi Talib, Najaf: al-Maktabat al-Haydariyyah, 1956.

Isfahani, Ibn Marduyah, Manaqib Ali b. Abi Talib wa ma Nazala min al-Qur'an fi Ali, Qom: Dar al-Hadith, 2001.

Kufi, Abu al-Qasim Ali, al-Istighathah fi Bid' al-Thalathah, Tehran: Mu'assasat al-Alami, 1953.

Kulayni, al-Kafi, Tehran: Dar al-Kutub al-Islamiyyah, 1988.

Qummi, Ali b. Ibrahim, Tafsir al-Qummi, Qom: Dar al-Kitab, 1984.

Laroui, Abdullah, Historicism and Tradition, Ankara: Vadi Yayınları, 1993.

Maqrizi, Abu Muhammad Taqi al-Din, Imta' al-Asma bi-ma li al-Rasul min al-Anba wa al-Amwal wa al-Hafadah wa al-Mata', Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 1999.

McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed), "Aisha bint Abi Bakr", The Encyclopedia of Qoran, Leiden-Boston-Cologne: Brill, 2001.

Mas'udi, Abu al-Hasan Ali, Muruj al-Dhahab wa Ma'adin al-Jawhar, Beirut: al-Maktabat al-Asriyyah, 2005.

Nawawi, Abu Zakariyya Muhyiddin, Tahdhib al-Asma wa al-Lughat, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 2007.

Oral, Mustafa, Meşrutiyetten Cumhuriyete İktidar Odaklı Aydınlar, Istanbul: Yeni İnsan Yayınevi, 2017.

Pugliese, Stanislao G., Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.

Safadi, Abu al-Safa Salah al-Din, al-Wafi bi al-Wafayat, Beirut: Dar Ihya al-Turath al-Arabi, 2000.

Sayyid al-Mar'ashi, Sharh Ihqaq al-Haqq, Qom: Manshurat Maktabat Ayatollah al-Uzma al-Mar'ashi al-Najafi, 1985.

Sijistani, Abu Dawud Sulayman, Sahih Sunan Abi Dawud, Riyadh: Maktabat al-Ma'arif, 1998.

Spellberg, Denise, Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past, The Legacy of Aisha bint Abi Bakr, New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Streitfeld, David, Ursula K. Le Guin, The Last Interview and Other Conservations, London: Melville House, 2019.

Suyuti, Jalal al-Din, al-Durr al-Manthur fi al-Tafsir bi al-Ma'thur, Cairo: Markaz Hijr li al-Buhuth wa al-Dirasat al-Arabiyyah wa al-Islamiyyah, 2003.

Sharif al-Murtada, Rasa'il, Qom: Dar al-Qur'an al-Karim, 1984.

Shawkani, Abu Abdullah Muhammad, Nayl al-Awtar min Asrar Muntaqa al-Akhbar, Riyadh: Dar Ibn al-Jawzi, 1427 AH.

Shaykh Mufid, al-Masa'il al-Sarawiyyah, Beirut: Dar al-Mufid, 1993.

Tabarani, Abu al-Qasim Sulayman, al-Mu'jam al-Kabir, Cairo: Maktabat Ibn Taymiyyah, 1994.

Tustari, Muhammad Taqi, Qamus al-Rijal, Qom: Mu'assasat al-Nashr al-Islami, 2004.

Ward, Baqir Amin, Ashab al-Hijrah fi al-Islam, Beirut: al-Dar al-Arabiyyah li al-Mawsu'at, 1986.

Ya'qubi, Abu al-Abbas Wadih, Tarikh al-Ya'qubi, Leiden: Brill, 1883.

Yücel, Ahmet, "Kitabet", Ankara: DİA, 2002.

0 Comments